OK- I have several other things I’d like to discuss: some thoughts from my current reading material, First, Break all the Rules and some thoughts on the UK’s announcement that it will probably withdrawal from Gemini and what it means to the Observatory, for example, but I thought I should close out my bit on the Scientist Dilemma and the Management Corollary from my 2008 SPIE paper first. Here, then, is how I introduced the Management Corollary in that work:

Scientists are not usually trained as mangers and managers are not usually trained as scientists. There are some talented people who can play both roles, but rather than relying on the exception, it is safer to plan for the more commonplace scenario.

Like software engineers, professional managers exist for a reason. They are trained in evaluating personnel, logistics, scheduling, fund-raising, etc. — all things not usually found on the transcript of your average scientist. On the other hand, they are not always well-versed on the science of their missions and less able to make well-informed compromises between a project’s logistical and scientific needs. The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope project is addressing this problem by putting both a trained scientist and an experienced manager in each management box of their organizational chart. This approach seems sound and time will tell how well this works, but the important point is to recognize that science leadership and management leadership are two different things and it is rare to find someone sufficiently effective in both.

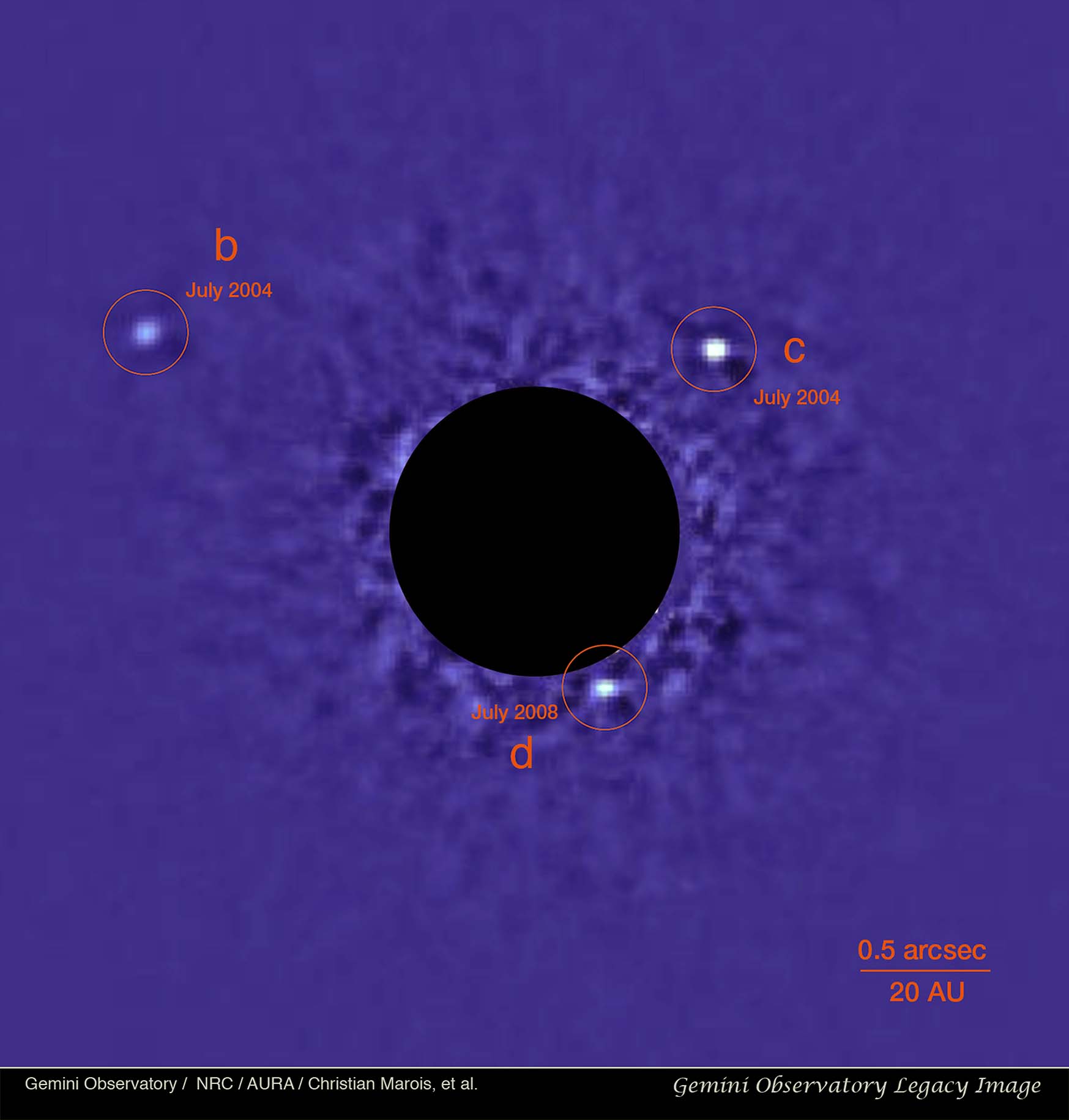

One of the first images of an extra-solar planetary system from Gemini Observatory. A result like this requires great efforts by individual scientists and project management to make happen.

Now I am going to venture off into even more generalizations – a habit which often gets me in trouble – but I think the generality addresses a point that we need to address. Compounding the problems described above even further is that scientists and engineers are often actually resistant to even the idea of management. For one, our lengthened education and noble “search for the truth” sometimes makes us feel that our efforts are above the need for management. Second, most of us went into science and related technical fields to actually do things; not manage things. If we wanted to manage things, we’d be wearing our pressed-shirts and jackets, working 9-5 and making more money (I know that’s not fair to the “real-world” managers out there, but hopefully you see my point). Our rewards and training have both been for doing things, not managing others to do things. Those who don’t do are often looked on as necessary, at best (and usually not even that), and certainly with a little disdain as well. Let’s face it, as a group, we don’t respect management. We feel our motives and aspirations do not require management and we want do to things – in line with our own vision of how to reach the truth – not manage things, or worse, be managed to do things.

So where does that put us? We are not trained as managers, we don’t like to manage, we don’t like to be managed, and we don’t really even respect the field of management, yet we work on projects costing untold amounts up to hundreds of millions of dollars and involving communities of thousands of users across multiple countries and cultures. I’d say there’s a lot to be done to improve the role, visibility and contributions of effective management to astronomical projects at all points in a person’s career – from school education through project initiation, completion, and operation. Granted, there are many good managers in astronomy and most large projects appreciate and exert good management, but management in astronomy still has a deeply seated reputation problem and we have still have many managers who continue to try to do rather than facilitate others to do. So here again is part of the reason for this blog – to talk about the role of management in astronomy and to discuss how to best find and employ the experiences and talents necessary to complete large astronomical projects as efficiently, accurately, and completely as possible.

Like most managers in astronomy, Scot didn’t start out thinking he’d end up managing astronomical projects (pun intended), but has found it a nonetheless interesting career path. He still tries to do, from time to time, and is currently working on a new catalog of White Dwarf stars which will about multiply the number of known white dwarf stars by a factor of two from the last catalog and a factor of 7 from 5 years ago. Although this desire to still occasionally do may make him part of the problem described above, he thinks some commitment to doing is healthy and can directly contribute to a astromanger’s management success, an idea for another post, most likely.